Overview

Panther is a distributed, (mostly) compliant, web-crawler written in Python.

In English: Panther is a service that lets you slowly download/index the web piece-by-piece.

In a nutshell, the way it does this is using an algorithm called BFS. If you think of the web as an actual web like below (with urls as points and links as edges), then what Panther does is start at a point and slowly expand from that center by visiting its closest neighbors.

Motivation

Last year, I made nearly the same project as a homework for a class. The result was pretty exciting, but everything felt super rushed. All the small things that I never fixed stayed broken after the deadline so I decided to bring it back and do things better this time. I wanted to focus on:

- bringing a better workflow (for debugging and benchmarking)

- adapting my solution so it actually works in a multi-threaded environment

- using the mercator style approach to crawling the web

After about 3 months of non-continuous work, Panther pulls off all of the above in a complete package.

Tech Stack

Summary:

- Flask: web frontend

- Celery: distributed task management (crawling itself)

- MongoDB: database

- RabbitMQ: message broker (url-frontier)

- Docker-compose: connect everything together

To change things up, I wanted to see how powerful Python would be for a project like this. I didn’t really want to worry about low level concerns like mutexes, locking and threading, so I thought it would be fine to adopt a framework like celery.

Celery is a distributed task queueing framework – which means it wraps tasks that need be done (the queues) and distributes them to workers to do them. Celery is what I’m going to be using for the heavy lifting of the crawler.

Mongodb is a database framework we’ll use to store the documents we see.

RabbitMQ is another kind of storage, except its meant for faster retrieval of smaller content – this is our message broker. It will relay the urls we need to crawl to celery.

Finally, since there’s so much going on, Docker/docker-compose – a piece of software used to run apps in different containers – will be used to piece everything together.

Architecture

There are two pieces of architecture to consider:

- The crawler architecture (efficiency)

- The overall service architecture (workflow)

Crawler Architecture

Let’s address the first one first. What a crawler does is the following:

1. Get a url that we need to crawl (from a queue)

2. Get the html/content for that url

3. Extract all of the links and add them to the queue to be also crawled.

4. Download the html/content.

5. Keep going

But to be compliant i.e. a friendly web crawler that doesn’t overload a domain with requests, each url crawled should also follow the robots.txt for that domain to see if they can 1. crawl the url in the first place 2. should wait a certain number of seconds before making another request to the same domain (this is called a crawl-delay).

At a high-level, this is our new process:

1. Get a url that we need to crawl (from a queue)

2. Check the domain's robots.txt to see if we can crawl this url.

If we *can* crawl:

3. Get the html/content for that url

4. Extract all of the links and add them to the queue to be also crawled.

5. Download the html/content

If we can't:

6. Skip it if robots.txt says we can't crawl or wait the required number

of seconds if it's a crawl delay problem. Eventually get to good condition.

7. Keep going.

Finally, to be less wasteful for duplicate urls, we should check to see if we’ve seen a url before AND if it’s content changed before we waste energy downloading the url.

Our complete process is below for reference:

1. Get a url that we need to crawl (from a queue)

2. Check the domain's robots.txt to see if we can crawl this url.

If we *can* crawl:

3. Also check to see if we've crawled this url before and if it hasn't changed

since we've last crawled it. If it hasn't, skip to 5 using stored copy.

4. Get the html/content for that url

5. Extract all of the links and add them to the queue to be also crawled.

6. Download the html/content

If we can't:

8. Skip it if robots.txt says we can't crawl or wait the required number

of seconds if it's a crawl delay problem. Eventually get to good condition.

9. Keep going.

Ultimately, the important part is that many of these steps can be done at the same time for many urls. I should have to wait for one url to finish downloading when 10 other different urls in the same stage could also be working.

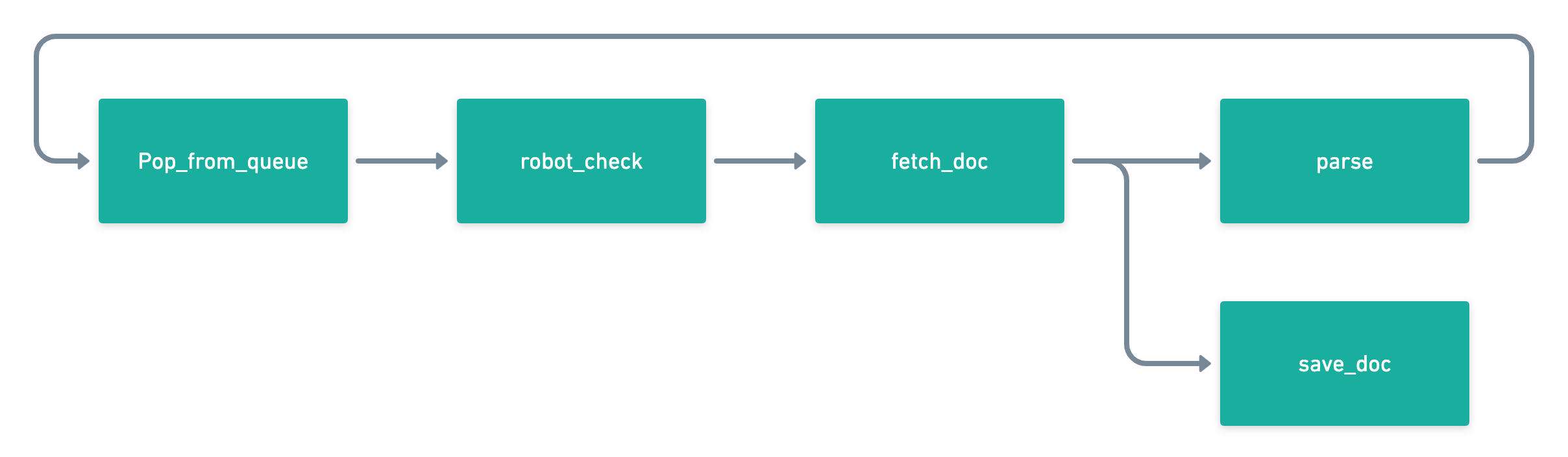

Namely, if we group steps 1 + 2 (robot_check), step 3 + 4 (fetch_doc), step 5 (parse) on its own, and step 6 (save_doc) on its own, we can build a pretty efficient workflow that can run concurrently without deadlocks/race-conditions:

This is exactly what Panther does, using celery to manage the queue of urls, and the distribution of work to each task. Each task above i.e. robot_check can be written as a python function that celery understands and can parallelize.

Workflow Architecture

Now, if we did everything above, we’d have a working product, but it would take forever to start up and even test. How do we really know how we’re doing?

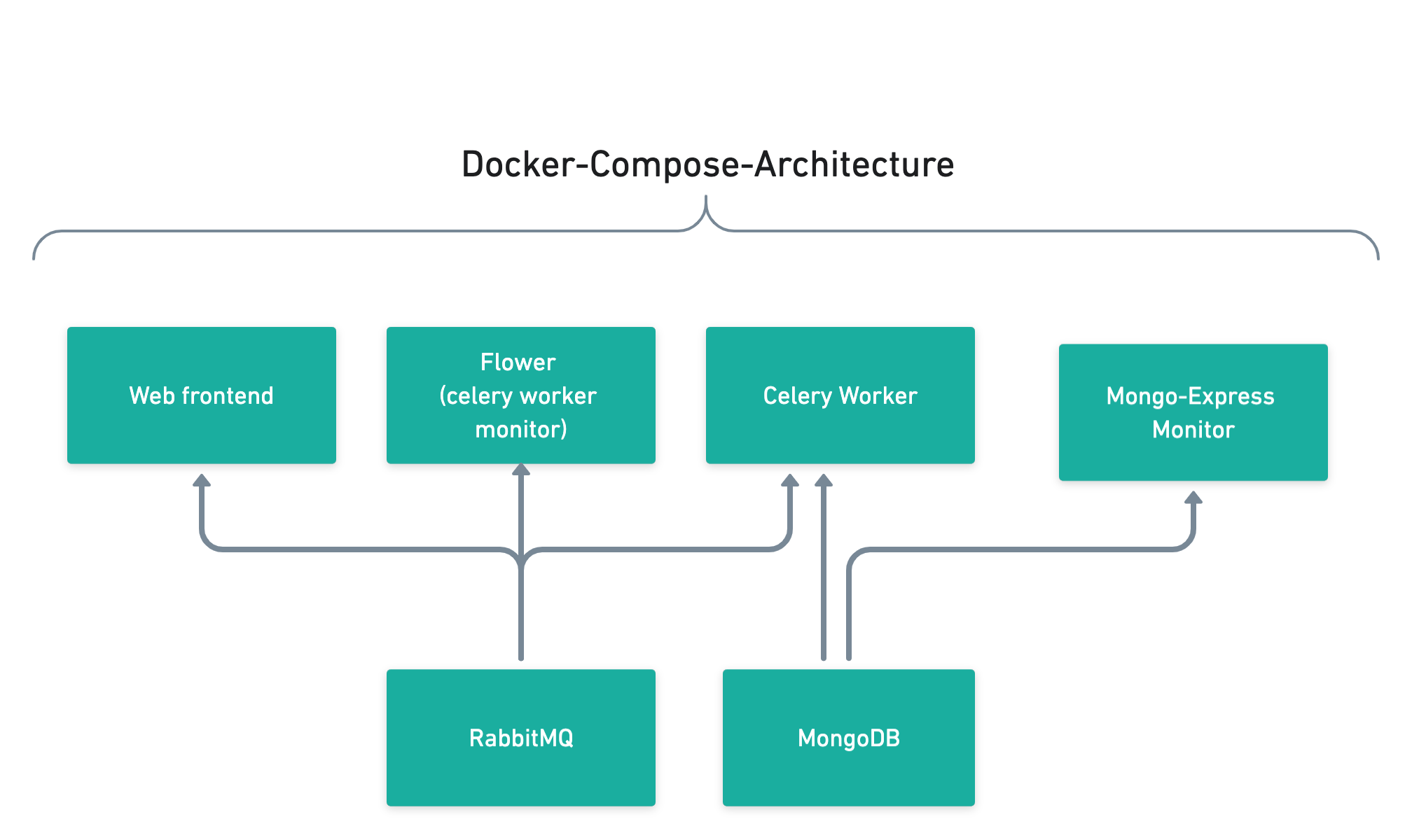

In the above case, we have three main things that have to run at the same time:

- The crawler i.e. a celery worker that handles tasks

- The RabbitMQ store, which stores our url queue and the other queues.

- The MongoDB store, which stores every document we crawled and other useful information.

But, even with all of this running, how do we add the first url? How do we check to see how many urls are in the frontier, or how many documents/which documents we’ve crawled?

At the worst case, we should want:

- The crawler i.e. a celery worker that handles tasks

- The RabbitMQ store, which stores our url queue and the other queues.

- The MongoDB store, which stores every document we crawled and other useful information.

- A monitor for the celery worker’s progress.

- A web client to view the contents inside the MongoDB instance.

- A web frontend that allows us to add a starting url or another url to the queue.

Instead of running six different terminals, we can use docker-compose to tie all of these services together and quickly start everything up. Altogether, our project looks like this:

The best part is that we can easily scale the number of celery workers, and check how everything’s doing. For example, I noticed that checking for the robots.txt every time for a domain is super inefficient, so I decided to store the robot.txt information in MongoDB to save bandwith and time spending reading the file. Using barebones stopwatch methods, you could pretty clearly see the improvement.

Conclusion/Reflection

This project was way more work than I initially expected. In all honesty, there were many times when I wanted to give up, since I felt like I was bogged down by problems I didn’t want to solve. Ultimately, the biggest lesson I learned is to set more clear goals/paint a better picture for what I hope will eventually be the finished product. For example, I never expected the final product would even have multiple docker containers running. Taking the time to think about what success would look like would’ve saved me hours of contemplating unexpected roadblocks.

There were many small details I skipped over, and since it’s way less consumer-facing than my last project Blanche, I didn’t really know how technical/tutorial-esque I should be with this post.

Ultimately, I tried to keep Panther’s code base super small and neat, so feel free to use Panther as a guide if you:

- want to or need to use celery to offload work in a web app you’re designing. Pay attention to how the flask

app.pycan add a task which a celery worker can pick up. This isn’t magic. By linking access to the RabbitMQ broker whendocker-compose'ing, the flask app can add to the queue that the worker can then pick up in a completely different container. - want to solve a distributed systems problem which ties multiple queues or follows a workflow

- want to know how to actually deploy celery as a service and tie them with other containers like RabbitMQ or MongoDB

However, just so we’re clear, there are some unclean things to look out for:

- Ports and urls shouldn’t be hardcoded. Always use docker environment variables.

- This crawler doesn’t delay between the HEAD/GET request for the same url in the pipeline (when it probably should). Still working on that.

Hope you enjoyed!